Textile Craft in Anatolia

- CTR

- Jan 7, 2015

- 7 min read

Introduction

During a research stay[1] at the famous Bronze Age site Kültepe/Kaneš, Turkey, Cecile Michel, Catherine Breniquet and Eva Andersson Strand had the opportunity for a one day visit to see some textile craftspeople in Anatolia. In this report we have decided to take out the names of the families we visited in order not to exploit their hospitality in a public forum. Still we hope that our readers will get an understanding of the amazing knowledge which is lodged not just in a single person but in the whole family across generations and genders.

Tuesday, August 5, 2014 - 10.45

We leave Kültepe by car together with Sezai Arık and Yağmur Heffron (research fellow at University of Cambridge), who kindly came with us and translated all conversations.

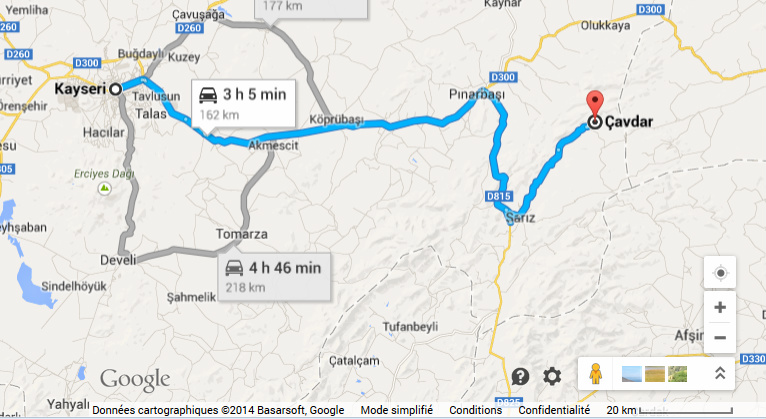

Sezai’s family is from the village of Çavdar (figure 1 see bottom of page), close to the city of Sarız, and knows both the area and the people very well. In Çavdar (figure 2 see bottom of page), we met with Ahmet Daldı, an old friend of Sezai and the owner of a café, nicely decorated with old Kilims and old tools. On the wall hung a carpet of about 100 years old, made in tapestry technique[2] in two pieces with drawings called “flowers”, “angry women”, stylized birds, etc. He explained to us that in the past, these Kilims were used to close the doors or to decorate the walls.

Ahmet had contacted local weavers and first he took us to a lady in this village.

25 years ago there used to be a loom in each house, in the village. However, people left the village and migrated to big cities like Kayseri. Slowly, from 1990 and on, textile craft disappeared. However, everyone still knows the technique, women and men, even if they do not weave.

Previously, revenues of families were 60% from herding and 40% from weaving. Still, families used to help each other, and if needed the female neighbours would come to help in finishing a carpet. In the past, homemade carpets were sold to make a living. Weaving is in general feminine activity, but all men know the techniques and can explain them. We were told that one man used to weave with his wife and that all the other men laughed at him, however, they stopped laughing when they realized that he was making a lot of money.

We went to the house of a wonderful woman who told us that she started to weave when she was 25. However, the extremely high quality of her work clearly shows that she has a very long experience and we think that she started to weave for sale at the age of 25. She has three sons and one daughter.

Forty years ago, the woman’s mother used to spin and weave, but nowadays, women use spun wool bought from Maraş. Previously, she said, the spinning was done with a wooden spindle which consisted of one spindle and two wooden parts slightly curved, crossing each other also called Turkish spindle (figure 3 see bottom of page). She also showed us a 150-year-old high whorl spindle in decorated wood[3] (figure 4 see bottom of page). She uses this spindle to create a strong 2-ply yarn for warping. She also had two weaving combs for beating the weft. The combs are made of iron and quite heavy, which must have facilitated the weaving and made it easier to pack the weft threads. Additionally the teeth were very short.

The woman does the warping during summer and weaves during winter (November to March?). She sets up some 10 metres of warp at one time which is used to make 4 carpets. It takes her only 1½ hours to set up the loom. The loom she is using is a large vertical two beam loom, big enough to weave up to c. 1.20m in width. All parts are made of wood and the loom is c. 1.8m. in width and c. 1.8m in height (figure 5 see bottom of page).

Her working weaving days start at 8am and end at midnight. 90% of the weaving is indeed done in the winter. The loom she is using was about 30 years old.

It takes her some 15 days to weave a Kilim of 1.20 x 3.80m. For a smaller carpet of 0.80m x 1.30m, it takes her 3 days.

The patterns she inserts in her carpets are suggested by merchants who bring models.

For private consumption, especially gifts for weddings or dowries, carpets usually bear the initials of the weaver. She wove a carpet for each of her sons for when they got married; such carpets are thinner than those produced for trade. She and her daughter wove the carpet for the daughter’s dowry together.

There has been a local initiative to create weaving courses to maintain the tradition, but there is a bureaucratic problem to solve; teachers must have diplomas and these weaving women do not have diplomas. This might be solved next year.

Damızlık

We next visited the village of Damızlık (figure 6 and 7 see bottom of page), twenty kilometres further and higher up the plateau.

There, it is still possible to see some traditional practices, like drying the dung for fuel, or drying straw on the roof of the houses. We visited two houses inhabited by two cousins. They belong to a pastoral clan originating from Çukorova. They have a large family with a lot of children. The first house is very big and decorated with a lot of homemade fabrics, carpets, Kilims on the benches, and friezes on top of the walls. The friezes are woven on the same looms at the same time as the carpets. They leave a space on the side of the loom and weave the bands separately. The tassels are added when the bands are finished. Such bands are only woven and used by the family.

The women weave on temporary looms. The warping is done during the summer and taken inside the house during the winter for the set up and the weaving. 90% of the weaving is done in winter.

They use the same kind of two-beam loom as used by the woman we first visited. They call it a “weaving tree”. They usually set up 10 meters to make several carpets. They weave between November and April[4], and disassemble the looms in April.

When someone in the family dies, the family gives a carpet to the mosque, this allows the mosque to renew its carpets.

They showed us many carpets made by the women of the family. Even though, most of the explanations were given by the men.

The most extraordinary was a long coloured carpet made by the grand-mother (?), and which was some hundred years old (?). At that time, they use to have their own herds, to shear their sheep in spring, to wash and prepare the wool, to spin, to dye the threads and then to weave. It took thus some 7 years to finish this carpet.

Girls weave with their mother for their dowry. It takes 10 days for 3 or 4 women to weave a carpet of 2 x 4m. They usually weave old traditional patterns.

In the 2nd house was a similar big carpet, with the same motifs as the one made by the grand-mother in the 1st house, but this one was about fifty years old.

For a carpet of 3 x 1.5m, 3 women work for 4 days: two works on the edges and one on the inside.

In one winter, a family would produce 25 carpets, but according to the head of the family, only 2 or 3 women do weave for trade in their families.

Both houses used iron combs with very short teeth made at Maraş, similar to those of the first woman we visited. A small “museum” was set up for us in the first house, where traditional tools were preserved, for example: iron combs, a Turkish spindle, a high whorl spindle with a square spindle, a male vest made with old Kilims, a churn, miniature trolleys, metallic vessels, etc. In the first house they still prefer to eat from traditional brass vessels.

Ten years ago, these families had still their herds, and they used wool for the Kilim, milk for private consumption, etc. When they were spinning, they needed 4 days to spin 1 kilo of wool, a carpet weight some 4 to 4.5 kilo à so 16-18 days to spin enough thread for such a carpet? However, today they have sold their animals because keeping livestock was no longer profitable. Instead they get their wool ready spun from Kayseri traders, who also give them the patterns to follow. However, they go to the dye man to buy natural dyes and they dye the threads themselves. The colours are their own choice which makes every piece unique.

They also had goats, and they use to make the Bedouins tents using the goat hair. They used the same spindle to spin wool and goat hair and probably also the same type of loom.

Sheep and herding

Usually the first snow appears mid-December or January. During the winter they feed their animals with barley and rye, 30% of the fodder was bought while 70% was pasture food. In the Spring the herds went up to the mountain as soon as the snow was melting and the sheep were running out of fodder in the Spring. At night the shepherd kept the herd on the top of the Plateau, 3-4 km away from the farm. He went up around 3-4pm and he came back with the herd before it became too hot. Sheep and lambs were kept separately.

Each family used to have its own herd and they had 40 to 50 sheep for 1 ram. In October the ram was herded together with the sheep and the birth of lambs took place in June. The wool was used for domestic purpose and sheared in July. The best wool comes from well fed males, not from females, but they used the bad wool to make mattresses. The age of the animal is not important for the quality of wool. They said that it is not the quality of wool which is the most important but the good skill of the spinner. Further, the same wool is used for both the warp and the weft.

Conclusion

It was a most wonderful experience to see the textile craft in Anatolia, and we warmly thank all the families that let us into their homes and demonstrated their amazing skills and knowledge and textile craft that have passed on for generations first hand.

The tour was arranged by Fikri Kulakoğlu (Ankara Üniversitesi, Director of Kültepe excavations) and Sezai Arık, (archaeologist from Kayseri Museum) whom we kindly thank. We also thank Sezai Arık and Yağmur Heffron for their guiding and for helping us with translations etc.This became a day we will never forget and a day when we learned a lot and we look forward to a return visit.

[1] In August 2014, Cécile Michel (CNRS Nanterre), Eva Andersson Strand (CTR, Copenhagen), Catherine Breniquet (Université Blaise-Pascal, Clermont-Ferrand) and Fikri Kulakoğlu (Ankara Üniversitesi, Director of Kültepe excavations), worked together on the field at Kültepe (Central Anatolia) on a joint project ( from 2013) within the frame of the French – Danish PICS TexOrMed. This project, which is based on the study of textile and basket imprints on clay artefacts from Kültepe Early and Middle Bronze Age levels.

[2] Known in Anatolia as Kilim.

[3] Geometric pattern on the upper part of the hemispherical whorl.

[4] April = winter season.

Comments